The PBS Hawaiʻi Livestream is now available!

PBS Hawaiʻi Live TV

Original air date: Tues., Mar. 4, 2008

The Late Samuel P. King was the son of a Hawaii Governor and he lived a life of public service. His father, Samuel Wilder King, served in the U.S. Navy during two World Wars and as delegate to the U.S. Congress and Governor of the Territory of Hawaii.

In 1997, Judge King found time to coauthor a lightning-rod newspaper essay with three other highly regarded Hawaiians and a law professor. The essay, Broken Trust, charged gross incompetence and massive trust abuse by the trustees of what was once called the nation’s wealthiest charity, Bishop Estate, responsible for the Kamehameha Schools.

Transcript

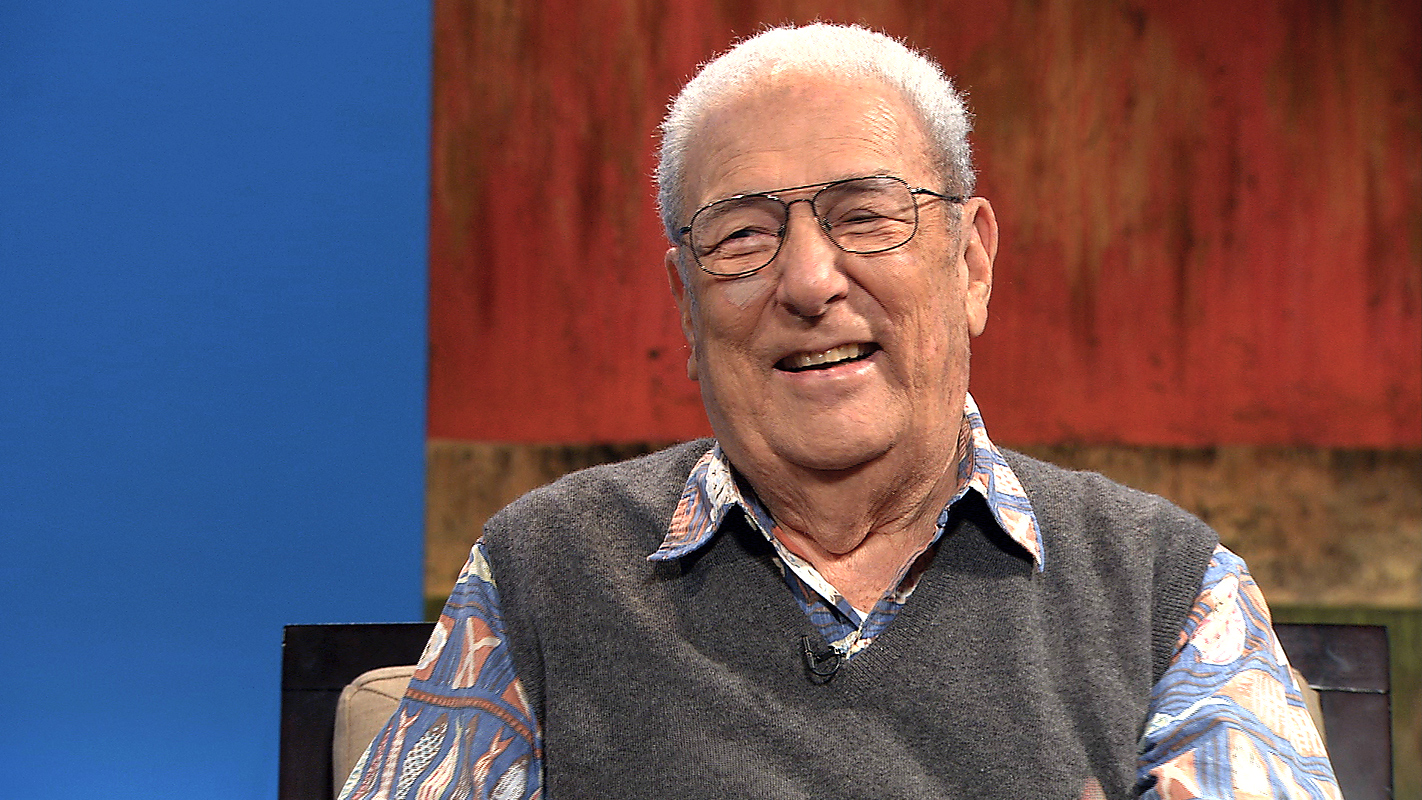

Aloha and mahalo for joining me for another Long Story Short. I’m Leslie Wilcox. Today we get to hear stories from Senior Federal Judge Sam King.

Samuel P. King was the son of a Hawaii Governor and he’s lived a life of public service. His father, Samuel Wilder King, served in the U.S. Navy during two World Wars and as delegate to the U.S. Congress and Governor of the Territory of Hawaii. Judge King is now in his 90s and he’s still a working judge, still hearing cases. In 1997, he found time to co- author a lightning-rod newspaper essay with three other highly regarded Hawaiians and a law professor. The essay, Broken Trust, charged gross incompetence and massive trust abuse by the trustees of what was once called the nation’s wealthiest charity, Bishop Estate, responsible for the Kamehameha Schools. More recently, King and law professor Randall Roth wrote a book with new details of unchecked power.

It occurs to me that you’ve grown up in the hallways, the corridors of power. Your dad was a naval officer, and then he was an elected officeholder; he was the Territorial governor. Maybe that’s why you’re so comfortable with power.

No, I think I owe a lot of that to my mother who made sure that we kept our feet on the ground. And she taught us we were just as good as anybody. And people who had power never bothered me. I guess I never ran into negative power, where they did really do something to me that I didn’t want to have happen. That just didn’t happen to me, so I was lucky. And Hawaii was a very good place to grow up. We moved out to Halekou, which was across the street from where the cemetery is now on the way to Kane‘ohe. And we lived there; I grew up there. It was just wide open spaces. And Kane‘ohe Bay is such a beautiful place. The family we were in the line of inheritance from Mokapu. In fact, when the Army—when the Air Force or the Navy or the Marines, whoever it was, came along, they condemned it. But the King family wound up owning Mokapu when the intermediate people died. I think we got $75,000 for it.

When you were a little kid, did you have to choose between your Hawaiian heritage and the Caucasian side? Was that ever an issue?

No, but we had more Hawaiian influence. My mother’s brothers had formed a Hawaiian group themselves, just when they went with the National Guard to mainland and so forth. So my Uncle Tom played the steel guitar. He took the steel guitar to South America, and then my Uncle Doc played the ukulele, and Uncle Kane played the ukulele, and Uncle Luther played the guitar. So we used to have—at least once a week we’d have a gathering and they’d all play music and sing Hawaiian.

Both of Sam King’s parents were part-Hawaiian. The family traveled extensively to follow their father’s Naval career, which is how Sam King happened to be born in China. Once the family returned to Hawaii, King attended Central Grammar, Punahou School and Yale University. He earned a law degree from Yale as well.

When I came back, let’s see, what happened? Of course, I went to work for the Attorney General and then the Land Department and then for the City and County of Honolulu. I was a prosecutor at the City and County of Honolulu. There were only three of us when Pearl Harbor happened. And the military took over, so we didn’t have a job. So then I applied to go into the Navy, which was a little bit of a problem, because I only have one eye.

Why do you only have—you have a glass eye, right? How come?

Well, it’s plastic now; used to be done in glass. I got a little piece of steel in it when I was about six years old.

I can’t tell which eye it is. Okay.

It’s the one with emo—they always said—the story about the banker. You look into his face—the banker with the glass eye; the one with the emotion is the glass eye. And you know, the Lord did that. Because if He hadn’t done that, I would have gone to Annapolis, and my class would have been the one on those cruisers that got sank, sunk in the bay off of Guadalcanal. And so luckily, I survived that. So after the—when we got bombed in 1940, I applied to go back in the Navy. But I had to go to Washington to get a deferment for this. Because they were taking anybody into things that didn’t need two eyes. In fact, I don’t need two eyes anyway. And I got a waiver, and was put in—they wanted to put me in the legal end. I said, No, no, I don’t want to be a lawyer anymore. So I was in Naval Intelligence, and they sent me to New Orleans after training. Well, New Orleans, you didn’t know a war was on. Then I got a notice that they wanted people to study Japanese. Well, I’d gone Japanese school here, Hongwanji Mission on Fort Street. So I knew a little Japanese, so I boned up, and I went to Washington and got interviewed. And the expert who was clearing us, he handed me number one book that we used, Naganuma one to twelve or was Ambi number one. And he said, Read the first sentence. Well, I don’t know if he did that on purpose, but he gave it to me the wrong way. So I turned it over. And opened it from the back, you know, and kept going until I found the first sentence. And I could read Katakana, which was in Katakana. Kore wa kanji desu. So it had to be; this is a book, you know. So I said, Kore wa hon desu. I was on my way.

And that was to be fateful because that’s where you met the woman who would become your wife.

That’s right. Ann was in Washington, DC after she graduated from Smith, working for the Army. And she found that a little boring. So she applied for this, and she goes and sees the same guy. Well, she had to be about this close to see; she wore very thick glasses. So they took her glasses off and said, you know, Read the chart. So she walked up to it about his far. You know, A, E, I, O, U. Oh, well; he said to her, You’re Phi Beta Kappa? Yes. What did you study? Greek. You’re in.

So tell me about that first meeting and what happened?

Well, I was the only person that wound up at Boulder, who was already an officer. So I was a Lieutenant JG. So they thought I’d been sent there as a spy, actually. And so when the WAVs came in, I was assigned to drill them in Japanese. You know. So she was in the group. She looked good going and coming. I proposed in two weeks. And she said, Maa, which is the Japanese word for heaven forbid, you know. She said, Ask me again Wednesday. This was a Sunday. So I did. And she accepted.

How did you know? How did you know that should be your life mate?

Well, she was a Phi Beta Kappa graduate, I was looking for. And she was nearsighted. Now, she doesn’t wear those glasses anymore. And that’s what I wanted; brains and beauty.

Sam and Ann King have been married since 1942; and they have three children. After the war, King went into private practice and later made the move from lawyer to judge. Appointed to the State’s First Circuit and Family Courts and U.S. District Court, Sam King presided over highly-publicized cases like the notorious double murder on Palmyra Island and the conviction of reputed syndicate crime leader Wilford ‘Nappy’ Pulawa on income tax charges. Despite the seriousness of the issues, Judge King could generally be counted on to bring a little levity to proceedings.

You know, I didn’t see you in court until you were a Federal judge. And I know as a reporter who covered courts that you were the judge people wanted to cover at that time because you would make these wry remarks. And you were so comfortable in that courthouse, and backed by law, and it was fun to see justice take place.

Judicial humor has got to be very carefully used. I never used it at the expense of the parties or their lawyers. Because that’s a no-no. It’s serious business to them. So when I was able to make a wisecrack, it was about something else.

As a judge of character and a Federal judge, do you size people up pretty quickly in court?

Not too quickly. I give ‘em the benefit of the doubt.

But are you usually right with your first impression?

M-m, usually.

What made you decide to be a judge? You’re a lawyer.

Well, that’s an interesting point. Bill Quinn was governor.

M-hm. And he was—in fact, he was the governor after your dad was governor, right?

Yes. And he was the last Territorial governor and the first statehood governor. So, and I was going home across the the greens outside of the Capitol. And Bill Quinn was going home; he was going the other way. So he said, Sam, Sam. I knew him. He says, You want to be a district judge, a circuit judge? I said, Well let me get back to you. He said, Well, I need to know pretty soon. I said, Well, I gotta ask my wife first, and then I’ll get back to you. So we talked it over, and I told him yes, Monday morning.

You flirted with public office; didn’t you?

Well, I got involved with politics, of course, because my father was involved in politics. Back before I had become a judge, I ran for the House. And I didn’t get elected, but we elected three Republicans. So then when I was a judge—Burns had appointed me. When I came up for reappointment, he appointed me again. So then I decided to run against him. But he wasn’t going to run; it was going to be Tom Gill. When I left the court and announced for governor, he ran.

How important to you was it to be governor?

Well, I thought there were important things that had to be done, but I knew the world wasn’t gonna come an end. I don’t believe government does everything for you anyway. So what they do is—the whole purpose of government is to keep the place safe and take care of the little people.

You know, it seems as though you were very comfortable with the role of judge. Was there anything that really taxed you or was very challenging along the way?

Well, I always had a hard time with criminal cases ‘cause I’m very doubtful about the criminal system and the putting people in jails or one thing or another. I haven’t come up with a better solution. So when I went senior I said, No more criminal cases.

‘Cause you have sentenced plenty of people to prison.

Yeah.

Did you ever experience threats on your life, or did you start looking behind you and locking the doors, and—

No, no. There’s nothing much they can do to work up a hatred of the judge. The judge is only doing what the law says. As I always told them—the guards—I said, The people you gotta guard are not the jury and the judge, but the witnesses.

In 1997, King was approached by University of Hawaii professor of trust law, Randall Roth, with a draft of an essay for publication. It harshly criticized the trustees of Bishop Estate/Kamehameha Schools and fanned the flames of a scandal that would drive the trustees from office and lead to a wave of reform.

He asked me what I thought. I said, Well, yeah, it’s good stuff. But it won’t go very far if you’re the only person putting it out. And he said, Well, will you join with me? I said, Well, I have to ask my wife first. And she said, Absolutely. So I said, Yes, I will. But I said, Just you and me is not enough. Well, he said, who else do you recommend? I said, Well, Gladys Brandt. And she said, you know, Sam King’s with you? And he said, Yes. She said, Count me in. Because she was already trying to do something. And she said, And I’m gonna bring in Monsignor Kekumano, who also was involved in the ongoing problem. And then a little later, he called and said, Well, Walter Heen has been suggested. Oh, I said, that would be beautiful. He was head of the Democratic Party, I was head of the Republican Party.

So the idea was to present this very credible group of people with stature in the community.

Yes. The five of us got together and went through this, edited it and so forth. And then said, Let’s get it published! And we knew Randy had an ongoing relationship with The Honolulu Advertiser. But they weren’t ready to print it. They had to change this and they had to do that, and so forth. So we went to the Bulletin, and they printed it the next day.

Makes you glad there’s a two newspaper town.

Yeah. And the introduction is written, you know, by—

Yeah; Dave Shapiro, who said your—

Yeah.

–essay, your joint essay was a bare-knuckled attack on a powerful institution.

It was. But the reason we got out there was because the Kamehameha ‘ohana had already marched on the trustees for similar reasons. And it all but started by Nona Beamer who printed the first letter that complained about it.

Your essay and the work of others before you triggered enormous investigations.

That’s right.

Prosecution.

Yes.

And did it go far enough?

One of the problems was that the Supreme Court was appointing the trustees. And it became pretty obvious that they were picking people without going into enough publicity and public input. But the present system is unstable. The Supreme Court could take it back or the Probate Court could say, Well, I’m not gonna bother with all this nonsense.

What’s a better idea?

Turn it into a not for profit corporation with directors elected by the ‘ohana or a majority of them.

Why do you think that’s not happening?

Oh, I don’t know.

Kamehameha will—

Everything has to get worse before it get better.

Kamehameha points that out that, after all of that happened, and the trustees departed, they’ve really amped up their education outreach, they’re doing a lot more things, they’re more responsive. They went out and got a hold of folks who had been cut off by the previous trustee system, and they were welcomed back in. And so there’s a rejuvenation and a new direction, and I think a lot of people at the school say, Why dwell on this—let’s not worry about making—

Well—

–the past—

–I don’t know—

–people accountable.

—who’s dwelling on what. And I suppose there’s an honor in being a Bishop Estate trustee which would not apply to a person who was a director of a not for profit corporation. But every provision of Princess Pauahi’s will has been violated. Her will says there should be two schools; one for boys, one for girls. Now, there’s one school, although they call them the Kamehameha Schools. Probably a good idea. But you know, that’s not what her will said. And she said they should be taught the basic reading, writing, arithmetic. Well, they’re a college preparatory school. So where are the ones way down at the bottom? Now, it is true that wills that are passed for eleemosynary purposes, over a period of years change, because times change. But her will has not been changed. And the one way you could get it a little wider is with a not for profit corporation, as Robert Midkiff has pointed out. But of course, then you won’t have these individuals who call themselves, I’m a trustee.

You heard what former trustee Henry Peters’ comment was about all of the work that you did with your partners on this. He said, The group of Hawaiians who wrote Broken Trust are country club, high muckety-muck Hawaiians.

Well, his most famous saying that I know of is, If I did the things they wrote about in the book, I should be in jail. And my answer to that is, I agree with him.

What were—

They violated every provision of trust law that they could.

I think it was referred to as a personal investment club atmosphere.

Yeah; well, they were investing in the same things as the trust. Which is a no-no; and they kept that all in a secret safe.

There’s a lot that hasn’t come out about what happened in those days, isn’t there? A lot of sealed pages.

Well, there can only be so much in the book, you know. If that book how many pages are there; three hundred something? Including the index? If it were a thousand pages, nobody would read it.

Roy Benham had a very interesting quote—

Yes.

–in your book. He said, you know, Hawaiians are funny in a way, that if you waste their money, you steal their money, they let that go. But you try to hurt their children, and – watch.

That’s what happened. Especially the eliminating the outreach program. They fired people in two weeks for no—said they didn’t have the money. What do you mean they didn’t have the money? They had plenty of money.

You know, you’ve gotten some distance now. When you look back and you see what was done in those times at the old estate, what was the worst thing the trustees did?

The worst thing they did was they ran it as a personal, personal property. Raised their fees, they were getting a million dollars apiece. They said, Well, the law permitted it. Well, there was a provision in the law that limited the amount of fees that a trust could take; but overriding the whole thing is the law of trusts, which says you don’t get paid more than you are worth. And not a one of ‘em was worth what they were getting paid.

Only trustee Oswald Stender emerged from the furor with his good reputation intact. At the time, the estate of Princess Pauahi Bishop was estimated at $10 billion and its trustee appointments were paying nearly $1 million a year. In 2006, Judge King and Randall Roth, a UH professor specializing in trust law, followed up the newspaper essay with a book titled Broken Trust: Greed, Mismanagement and Political Manipulation at America’s Largest Charitable Trust . Today, King maintains a watchful eye.

More recently, I saw in the paper where they said they were going to help the homeless. There’s nothing like that in her will. Maybe as a not for profit corporation, they can do that; tie it onto something. But you know

So you still don’t think they’re going in the right direction?

They don’t seem to be aware of what they’re doing. It’s all right with me; I’m not gonna heckle ‘em anymore.

And that’s what your book shows; it shows the degree to which the power structure was interlocked with the old Bishop Estate trustees.

Yes. But get it away from the courts by having a not for profit corporation, where it has directors appointed elected by the ‘ohana, by the graduates.

Do you think that’ll happen in your lifetime?

No.

Think it’ll happen, ever?

Well I don’t know. It should. The one force that could handle it would be the IRS, which says, You’re not carrying out the provisions of your trust.

You know, your book has created a sensation in trust circles, you know, trust lawyers. I mean, you’ve gotten a very prestigious award, and so has Randy Roth. You know, they consider it a bible of what not to do—running an organization like that as a feudal empire. Do you think it’s gotten the attention and the action it deserves in Hawaii?

I don’t know. I haven’t followed up on that. But it is true that we got told by the University of Hawaii that a college had ordered several hundred books direct from them. Don’t know what they’re gonna do with them, but somebody thinks it’s useful for some purpose.

You’ve been in Hawaii working in the trenches and seeing the corridors of power for a very long time. When you look at what you know and what you think may be ahead, what’s your vision of the future? Are we doing all right?

We’re going to be more and more influenced by California. Both by people and by law. So eventually; that’s why I’m really a backer of OHA, because that’s one place where they can protect the future for our Hawaiians. And I interpret Hawaiian as real Hawaiians; not like me. What do I have; three-sixteenths? You know, I got an eighth from my mother, and a sixteenth from my father; three-sixteenths. I’m not talking about myself. Although emotionally, I’m with them. And naturally, I’m an official of the Federal government too.

So you see OHA as being an institution that—

Yes.

–can’t be touched.

Yes.

Except there are a lot of people who want to see those entitlements go.

Yes. There always are. I mean if we’re talking about a bunch of goodies going to be given to a bunch of people of which I’m not a member, well, I’m opposed to it.

And you’re still vigilant, hoping Kamehameha Schools changes its governance.

Oh, they’re okay. I’m not spending any time losing sleep over it. I think they’re spending more time opposing the idea, than I am promoting it.

When’s the last time you lost sleep worrying about something?

Gee, I can’t think. I guess it was between Sunday and Wednesday, when I was gonna call and she said, Ask me again Wednesday. So between Sunday and Wednesday, I lost a little sleep.

When you didn’t know whether your intended wanted to marry you.

Right.

She kept him guessing for a few days. In his 90s, Judge Samuel King continues to preside over federal court cases in Hawaii and California. I’d like to thank Judge King for sharing his stories with us. And thank you for visiting our website, emailing us with comments and suggestions and for joining me each week for conversations on Long Story Short. I’m Leslie Wilcox. ‘Til next time… a hui hou kakou!

What were your family names in Hawaiian?

Family names?

M–hm.

I’m the only one doesn’t have a recorded Hawaiian name. My sister, Charlotte, is Charlotte Lelepoki. And then my two brothers. And the youngest sister is Nawahine‘okala‘i. And in between is my two brothers, Evans Paleku‘ukana‘iaupuni and Davis Mauleolake‘awe‘ahe‘ulu.

You said you don’t have a recorded Hawaiian name. Do you have a nickname?

Kalani‘olumohi‘ikai.