The PBS Hawaiʻi Livestream is now available!

PBS Hawaiʻi Live TV

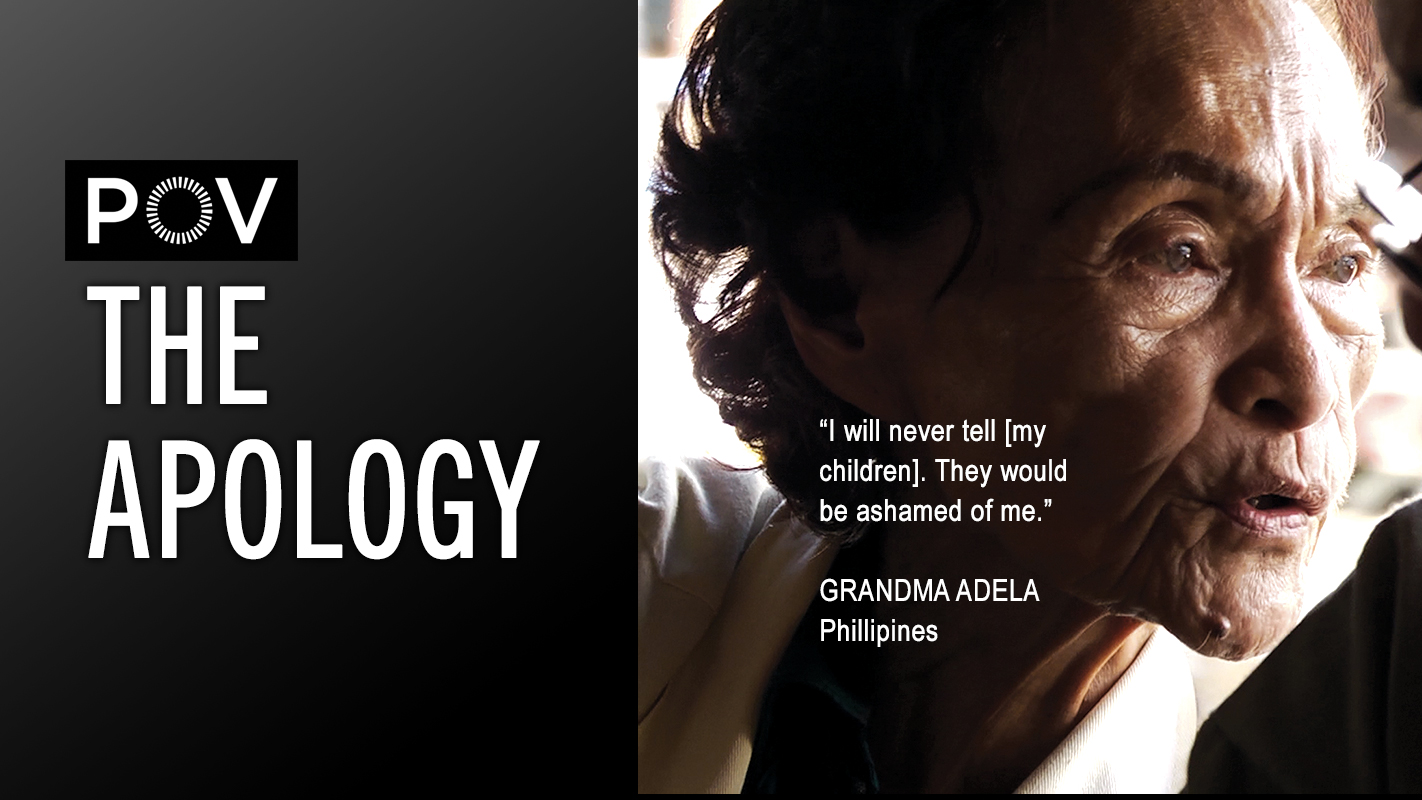

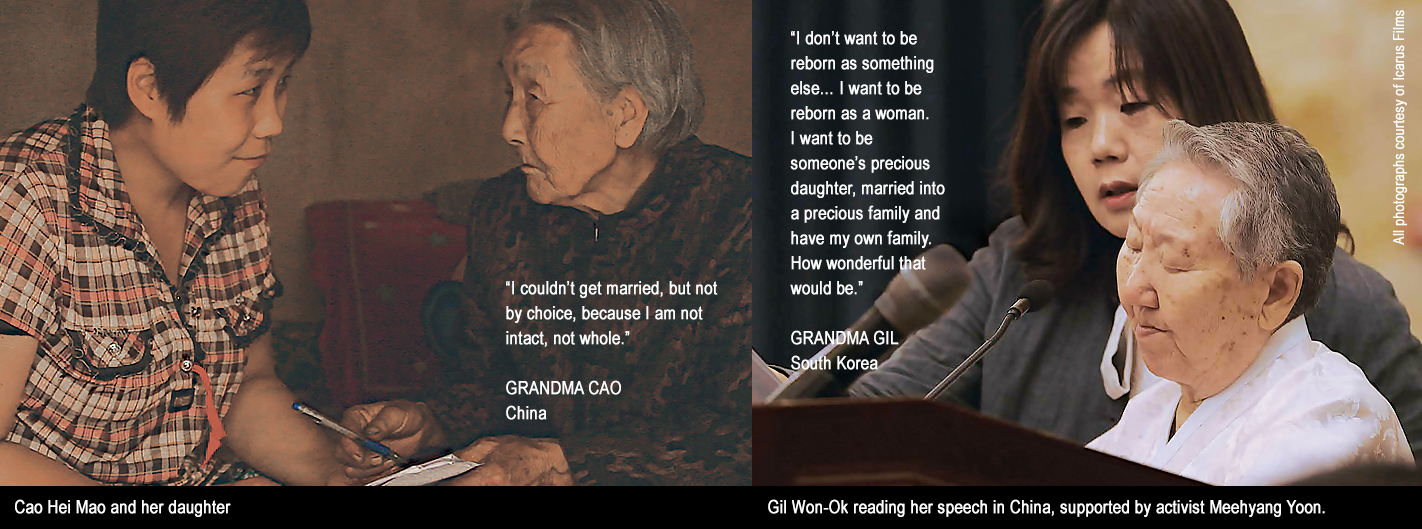

During World War II, the Imperial Japanese Army kidnapped approximately 200,000 young women and forced them into military sexual slavery as “comfort women.” The Apology follows three of these women – Adela Reyes Barroquillo in the Philippines, Cao Hei Mao in China and Gil Won-Ok in South Korea – in the ongoing movement pressing the Japanese government for a formal apology that has never come. Seventy years after their imprisonment, and after decades of living in silence and shame, these once invisible women (culturally referred to as “grandmothers”) give their first-hand accounts of the truth for the record in hopes that this horrific chapter of history will not be forgotten.

During World War II, the Imperial Japanese Army kidnapped approximately 200,000 young women and forced them into military sexual slavery as “comfort women.” The Apology follows three of these women – Adela Reyes Barroquillo in the Philippines, Cao Hei Mao in China and Gil Won-Ok in South Korea – in the ongoing movement pressing the Japanese government for a formal apology that has never come. Seventy years after their imprisonment, and after decades of living in silence and shame, these once invisible women (culturally referred to as “grandmothers”) give their first-hand accounts of the truth for the record in hopes that this horrific chapter of history will not be forgotten.

Filmmaker Tiffany Hsiung spoke with us by phone from Toronto, Canada about the film:

PBS Hawai‘i: Could you take us through the process of deciding to make this film and how it became, as you say, a film you “needed” to make?

I was appalled and shocked when I first heard about comfort women, mainly because I was already turning 25 and had never heard about them before. Bits and pieces of stories about WWII in Asia would be told by elders and family members, but they never talked about the sexual slavery that occurred.

I was invited by educators in North America to document teachers in Asia who were survivors. It was through that two week tour that I realized there was so much more to learn. I wanted to learn, not just about what happened to the grandmothers when they were comfort women, but about the aftermath. So many war stories focus on the act itself, when I think the six decades of surviving better illustrates the gravity and the impact of what they lived through. I knew we wanted to let the grandmothers take us on their journey. I knew I didn’t want it to be saturated with archival footage or scholars and historians talking about “the facts.”

I realized working on the project that my own silence and shame from my experience as a survivor of sexual violence was something I was still holding onto, and the grandmothers gave me the strength to come to terms with that. It was an organic process, and the film ended up being something I needed to make.

What kept you going, and what perspective can you give viewers to help them digest this emotional film?

It was difficult. I remember trying not to cry in front of the grandmothers, and when we filmed in locations they had been taken to, I had nightmares. There was only one time I felt like I couldn’t go on, and that was the passing of Grandma Adela. I was closest to her, and we had dreams of traveling with the film together. My greatest regret is that I wasn’t able to finish the film in time for her to see it, and the amount of love and support she got from audiences around the world. I know that would have made her so happy and proud.

What was important to me to bring across in the film was the human spirit of the grandmothers, the levity they brought to everything they were doing. There is so much life in them, and that is what got me through the hardest moments.

And where do you think their strength of spirit and levity comes from?

The human condition is both laughter and tears; we’re not just one emotion. After surviving what they had endured, the grandmothers just have so much love to give. They want to give to a new generation.

What are the newest developments for the Grandmothers’ and their movement?

Even though she says in the film that she wants to just eat and sleep from now on, Grandma Gil is still traveling to spread awareness for the cause. The grandmothers have also started the “Nabi” Fund (Korean word for “butterfly”), which they contribute to themselves to help women currently enduring sexual slavery or violence around the world.

The new Korean government is standing behind the grandmothers, aiming to create a new agreement with the Japanese government that listens to the grandmothers’ demands – mostly having to do with education. The “One-Million Signature” petition highlighted in the film is also still available to sign.

What would you like viewers to come away with after seeing the film?

I hope viewers will be inspired by the grandmothers, their resilience. I hope viewers can look into their own lives and see how they might be contributing to the cycle of silence and shame. It starts with our own families; you never know what a family member has been through. I hope they can open up a safe space for conversation about sexual violence.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.