Watch our livestreams: PBS HAWAIʻI PBS KIDS 24/7 NHK WORLD-JAPAN

Kū Kanaka/Stand Tall

The story of Hawaiian community leader Kanalu Young

By Liberty Peralta

In August 1969, 15-year-old Terry Young took a dive into the ocean from a rock wall at Cromwell’s Beach near Diamond Head. The water was shallow; Terry hit his head. In a split second, he became quadriplegic – paralyzed from the neck down, with limited use of his hands and arms.

In rehab, bitter from the accident, young Terry took his anger out on hospital staff. Eventually, he realized that his rage could destroy him – or he could learn a great lesson from it.

In rehab, bitter from the accident, young Terry took his anger out on hospital staff. Eventually, he realized that his rage could destroy him – or he could learn a great lesson from it.

It was 1970s Hawaiʻi, and the Hawaiian Renaissance was taking root. Terry, who would adopt the Hawaiian name, Kanalu, turned his passion toward Hawaiian language, history and culture. In the 90s, he earned a PhD in Pacific Island history and began his career as a professor of Hawaiian history at the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa.

Filmmaker and professor Marlene Booth first met Kanalu when they both served on a panel to review film proposals. They ended up working together on Pidgin: The Voice of Hawaiʻi, a documentary that made its broadcast premiere on PBS Hawaiʻi in 2009. Shortly before the completion of Pidgin in 2008, Kanalu passed away at age 54.

Marlene spoke with us about the making of Kū Kanaka/Stand Tall, and about Kanalu’s life and legacy. The following is a transcript of that conversation.

PBS Hawaiʻi: Tell us about when you first met Kanalu.

Marlene Booth: I first met Kanalu in the year 2000. We were both serving on a panel put together by PIC [Pacific Islanders in Communications] to judge proposals for films. He was there representing the academic side and I was there representing the filmmaker side. I saw that as we discussed the proposals we’d read, he and I seemed to be saying similar things, and I liked that, so I approached him and asked him if he ever thought of making a film. He was a professor, a tenured professor at the University of Hawaiʻi, but he said yes! He said yes as though he had been waiting for somebody to come and ask him that question.

So we began talking about, if we made a film together, what that would be. We emailed back and forth because I wasn’t really living here at that point, and came up with the idea to do a film about the resurgence of the Hawaiian language, which ended up morphing into a film about pidgin, because of Kanalu. This local boy, who taught Hawaiian studies, who loved Hawaiian history, and really felt like Hawaiian history and Hawaiian language had given him a sense of who he was in the most important way, said, “Let’s do a film about pidgin.” And when I asked him why, he said, “Because without pidgin, I would cease to be whole.”

So we ended up then making a film about pidgin, which was on PBS Hawaiʻi, called Pidgin: The Voice of Hawaiʻi. That took many years because funding a film always takes a long time, and producing a film takes a long time. Towards the end of the editing of that film, Kanalu passed away. He was quadriplegic from the age of 15, and almost a lifelong sufferer with asthma. With the combination, he got very sick. He ended up in the hospital and never came out of the hospital. We lost him in late August 2008. Pidgin would be finished just a few months after that, toward the end of 2008. Kanalu, unfortunately, only got to see the first 20 minutes of it, which he liked. But he would have loved to see the finished product. He would have loved interacting with audiences and talking to them about who they are. Identity was very important to him.

When did you realize that Kanalu’s story would make a good film?

A few years had passed [since his death]. I started thinking about Hawaiian language and history, and what it meant to live in a place like Hawaiʻi, a place where history is alive and being talked about every day. There’s such vitality to that and such importance in terms of what it means to be a person whose history is being rediscovered and affirmed. The renewed interest in Hawaiian language and history are really embodied in Kanalu’s life. He became active in the disability community as a leader, but he was well aware that all around him was the awakening of Hawaiian culture. It was as though what had been a Hawaiian Renaissance on a statewide scale became Kanalu’s renaissance. It completely opened him up to all of these things. Everything spoke to him and he wanted to grab it in every way he could. He became a graduate student in Pacific Islands history, which is what [UH] had at that point, and he got a PhD in it and became a professor.

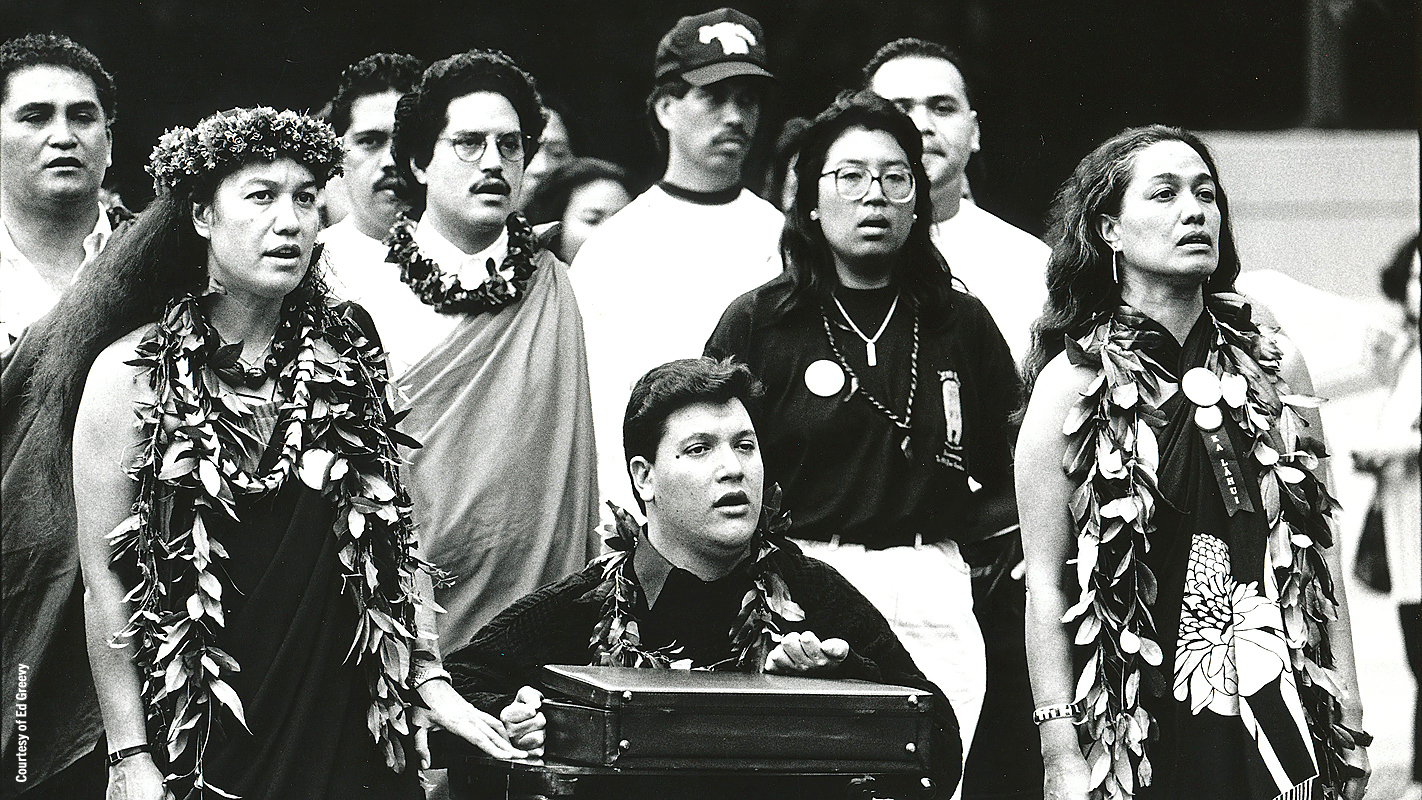

Kanalu Young, center, was in the front line of the 1993 ‘Onipa‘a march, which observed the 100th anniversary of the Hawaiian Kingdom overthrow. Photo courtesy of Ed Greedy.

Kanalu Young, center, was in the front line of the 1993 ‘Onipa‘a march, which observed the 100th anniversary of the Hawaiian Kingdom overthrow. Photo courtesy of Ed Greedy.

Meanwhile, he didn’t limit what he was learning to the classroom; he went to demonstrations. In one, which was a year before the famous 1993 ‘Onipa‘a march, in 1992, he was arrested at a vigil that was celebrating King Kamehameha on King Kamehameha Day. It was meant to serve as preparation for what would become the ‘Onipa‘a march the next year. People stormed the stairs of ‘Iolani Palace, which he could not do. He was forcibly pulled from his wheelchair and thrown in a paddy wagon, which I think brought him into the notice of people who might not have known him outside of the university. When the 1993 march came along, it struck a chord with people who, as [UH Hawaiian studies professor] Jon Osorio told me, had not heard the real history of Hawaiian history, and this was the first time they had heard it. At that march, Kanalu is in the front line. He suddenly goes from being a learner and a student who’s moving toward becoming a teacher, to becoming a leader, not having really thought it, but his actions that came out of his sense of who he was and what he had to do propelled him there.

The film presents parallels between Kanalu’s life story and the story of the Hawaiian community. Was this something Kanalu himself observed?

In one of the final interviews he gave, Kanalu was in bed, and he’s talking about how he thinks he has an unusual perspective on the Hawaiian sovereignty movement. He says that when he came into it, the Hawaiian community was broken and in recovery. He said, “I understood that.”

When I spoke to Noelani Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua, who had been his student, and Jon Osorio, who was his very good friend and colleague, both of them said something similar – that Kanalu brought to the Hawaiian movement a sense of understanding and moving forward from trauma because he had had his individual encounter with trauma years before. I think Kanalu knew that the recovery side doesn’t stop, it’s ongoing. I think he felt that the Hawaiian movement gained strength by acknowledging trauma, acknowledging loss, and moving forward to recovery. I think he felt that understanding history, re-asserting language, and publicly celebrating culture, was really very important to cultural and national renewal.

How did the film’s title come to be?

One of Kanalu’s friends who teaches at an immersion school, Pua Mendonca – I was talking to her early in my research for the film – I said, “What would you title it?” And she said, without missing a beat, “I would call it Kū Kanaka/Stand Tall.” She said Kanalu always stood tall. He was always head and shoulders above the rest of us.

I later learned that there was a book with that same title about the resurgence of Hawaiian music, at the beginning of the Hawaiian Renaissance. That came out many years ago, and yes, they both have the same title, but there was no connection.

Why is the film only about 30 minutes long?

There are several reasons. The funding mandated half an hour. There’s also only a finite amount of footage we could find of Kanalu that was in usable form. There was a lot of material on VHS that had deteriorated to the point of no recovery. I think we searched long and hard for any material of him.

We didn’t want him to get lost in the story. It’s tricky when you’re doing a film about someone who’s passed away. It’s easy for the film to be one person or another giving testimony about who he is. It was very important to have Kanalu’s voice and image in the film, and there just wasn’t all that much out there. What was out there, we found, as far as I know.

Half an hour is also a very usable length for classrooms and that’s important. Also, I realized that an hour-long film would have also been another year or two of fundraising and production. I really wanted to get the film done and out and used.

You worked a lot with ʻUluʻulu [the moving image archive at UH West O‘ahu] on this project.

ʻUluʻulu was so important. The film would not have happened without ʻUluʻulu. They were the ones really getting their hands dirty. They have a ton of footage from the ‘Onipa‘a march and Kanalu was in a lot of that.

ʻUluʻulu found an interview that Mahealani Richardson had done as a young reporter at KGMB asking him about ʻaumakua. The cameraman, bless him, let the camera roll before and after the interview. What Kanalu said to Mahealani before and after the interview became key pieces in the film. They talked as an older Hawaiian man who knew Hawaiian history, and a younger Hawaiian woman who was curious. I would have never found this footage without ʻUluʻulu.

What are some things about Kanalu that you wish could have been included in this film?

I’m happy with the film; it gives a strong idea of Kanalu and his importance to the Hawaiian movement. He loved to sing, and he had a wonderful sense of humor, and I don’t think we were able to get enough of that into the film. I wish there had been the time to develop more the fullness of Kanalu the person, but in finding a story, the strong focus seemed to be his individual understanding of who he was as a Native Hawaiian, and the way he was able to propel that into helping others connect to the Hawaiian movement.

And some things need contextualizing. There’s some home movie footage that Kanalu’s brother shot on VHS, where he’s being silly, but I think it would have taken a little bit of contextualizing to explain where his silliness came from and how it operated.

There was a whole incident that we never talked about [on camera]. Leading up to the 25th anniversary of his accident, of taking that dive at Cromwell’s, he said, “I want to go back to Cromwell’s. I want to get in the water and I want to make my peace with the ocean, and I want to reassert my love for the ocean and tell the ocean it wasn’t your fault.” He does this whole thing of finding friends who are lifeguards and firemen and weather people who can tell him what the surf condition is going to be, and then he mobilizes everybody he knows, and he works out a whole choreography. “How am I going to get in the water? What are we going to use?” And he does it! They get him in the water. The waves were coming over him because the waves were stronger than predicted. He does it for himself; he wants that experience. But he also does it for everybody else, to show them that anything is possible. It’s got to be tactile for him, even though he can’t feel most of it, except for his neck up.

Friends and family helped with Kanalu’s return to Cromwell’s Beach, 25 years after his fateful dive there paralyzed him from the neck down. Photo courtesy of the Family of Kanalu Young.

Friends and family helped with Kanalu’s return to Cromwell’s Beach, 25 years after his fateful dive there paralyzed him from the neck down. Photo courtesy of the Family of Kanalu Young.

If Kanalu was a different person, he could have said, “I never want to go back there.”

Exactly, but he wanted to, and it was fantastic. His friend and younger colleague, Kekai Perry, told that story, but I didn’t have Kanalu telling it. I had one great photo, but it just wasn’t enough to make a whole scene work in the film.

Each thing I might have added about him [in the film] would have uncovered another layer of this man. We can’t any of us be reduced to just one thing about ourselves. But in a film, of course, you need to have a goal and find a story. The more compelling story seemed to be who he was as a voice at this time, at that moment in history. Next film, next round. [laughs]

If there’s one message you’d like people to take away from this film, what would that be?

Boy, there are a million messages. Kanalu was both a gentle man and a warrior, and I think he understood that history is complex, the times we live in are complex, and we need to garner our strength to recognize injustice when we see it, to be resilient to fight against it, and to continue that engagement, while continuing to be ourselves.

In these times, I think he would say that there is strength in knowing who you are and knowing the various parts of yourself, especially for Native Hawaiians, in terms of knowing the history, language and culture, and understanding that those tools embolden you and make you a better person, and never to forget that, and to use that in service of fighting injustice.

I think about him all the time and what he would be making of our times now. And I think he would say, “No give up.”

Right after his accident, Kanalu was in the hospital, angry at everyone there. It would have been so easy to go in that direction instead.

He saw that other direction. But Kanalu makes a decision that you’re in rehab to not give up, and that makes all the difference. Once he’s made that decision, that he’s in the game and he’s in it for the long haul, the world opens up to him, and he goes after everything.

He was always open to new things. He could take a really strong stand publicly about something in Hawaiian history, and then he’d uncover new evidence. He was always saying, “It’s got to be evidence-based. Make sure that what you’re saying is evidence-based.” Every time I say that to my classes at UH, it’s Kanalu speaking through me. If he had evidence for something, he’d change his mind and not feel like less of a person.

He often said that if the accident had not happened, he would never had been who he became. Not that he would have ever looked for the accident, but it gave him a focus, and a seriousness of purpose, and a seriousness about himself. From that, he knew how to adapt to change. That was not something new for him; he had adapted to probably one of the biggest changes to adapt to, when he was just an adolescent, becoming who he was going to become.

Kanalu Young at an Elder-hostel (now called Road Scholar) summer program, circa 1997. Photo courtesy of the Family of Kanalu Young.

Kanalu Young at an Elder-hostel (now called Road Scholar) summer program, circa 1997. Photo courtesy of the Family of Kanalu Young.

He was comfortable with himself as a man in a wheelchair in public. That was never an identity he shied away from; he was who he was. His disability was a part of who he was. It gave him a perspective on himself, on life, on Hawaiian history, that he appreciated. It allowed him to see things and hear things and to understand things that might not be available to everybody.

A big life, this man had.