Watch our livestreams: PBS HAWAIʻI PBS KIDS 24/7 NHK WORLD-JAPAN

Growing up in then-rural Kapaa, Kauai, Edwin Gayagas was an adventurous toddler. He figured out how to harvest his own dessert -by pulling honey from a beehive behind his home at Kapaa Stables. He also made friends with soldiers whom he discovered camping in nearby pastures. That was shortly before America entered World War II. The soldiers would be a formative influence.

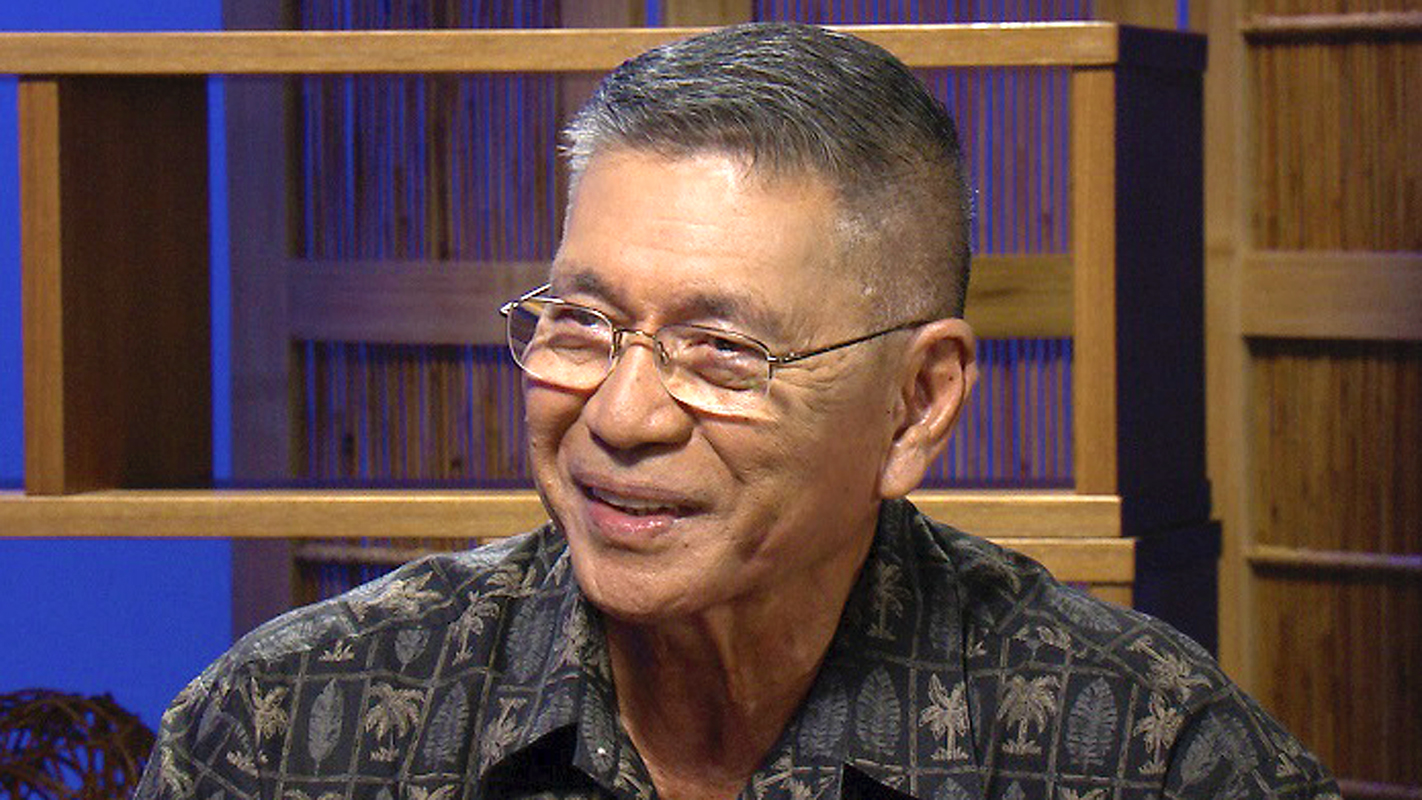

Ed recalls joining the Hawaii National Guard at 16, lying about his age to gain admittance. He pursued and lived his dream of a military career, serving in the U.S. Army around the world and rising to the rank of Colonel. Throughout his life, this fitness buff has maintained a positive attitude which helped him overcome challenges and which he still exudes in his 70s.

This program is available in high-definition and will be rebroadcast on Wed., Feb. 11 at 11:00 pm and Sun., Feb. 15 at 4:00 pm.

Transcript

My father started working at age fourteen, and had a knack for animals, as well as ability to deal with people. So, he became the stable master, and he also became the Camp 35, which was where all the bachelors lived, and he became the police officer for that area. He was only five-six, but he was quite a fighter. I found out that he could actually box.

Is that how he kept the bachelors in line?

I think that’s how he did it. But he was also very talented; he played the guitar, he sang. And I keep wondering; hey, where’s this gene that I need? I’m probably the only Filipino in the whole wide world that hasn’t got any rhythm.

Retired Army colonel Edwin Gayagas may not have had a knack for music, but he did grow up with a strong sense of determination and loyalty. These qualities took him from a small plantation on Kauai to a life of service to his country, and his community. Edwin Gayagas, next, on Long Story Short.

Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox is Hawaii’s first weekly television program produced and broadcast in high definition.

Aloha mai kakou. I’m Leslie Wilcox. Edwin Jose Gayagas, a retired colonel in the U.S. Army, was born in 1938 on the Island of Kauai. His father was a contract laborer for Lihue Plantation, and he lived with his family at Kapaa Stables. For Ed, as he prefers to be known, it was an idyllic place to grow up.

[MUSIC]

Life on Kauai was fabulous. It was great, and sure gave me great memories. It was a place that you could call the Garden of Eden in Hawaii. And we had mountains from the top five minutes away, and below was the ocean, five minutes away. And we lived in a small cluster of plantation homes. There were six Japanese, and one Filipino.

We were the only Filipino family.

And this is Kapaa; right?

This is Kapaa. And the Japanese families, one was from Okinawa, the rest were from Japan. They were all immigrants; they spoke mostly Japanese, which also helped me in speaking a little Japanese at that time. I can’t do it now, but I did at that time. What I used to do was visit each obasan … in the day, until I was about five years old. And so, I’d stop by, and they would offer me cookies, musubi, chicken; whatever it was. So, by the time I made the circuit and got home, I wasn’t very hungry.

[CHUCKLE]

And so, what happened was, my mom would always fix me a place at dinner. And at dinner, I would say, Oh, yeah, I’m hungry. I had to tell her I’m hungry. Wow, all this food has gotta be eaten on my plate. And so … I didn’t tell my mom until maybe seventy years later, when she was uh, ninety-three; I told her, Mom, I have a confession to make. You know all that good food you made for me at dinner that I ate? I actually was too full to eat at every meal. And so what I did; before I got to the table, I wore long pants. I got the food, I put it under the cuff and rolled it up all the way. And then, I’d say, May I be excused? And I’d go out to the chicken coop and I’d feed the chickens.

Oh! Well-fed chickens.

Yes.

What did your mom say when you told her that many years later?

She laughed, and she said, You naughty boy. [CHUCKLE] But the thing about feeding the chickens was their eggs. They always laid eggs. And my favorite meal after dinner or during dinner was a raw egg. So, I’d get the egg, I’d eat it, and then I’d go for my dessert. Over in the back side of our yard was a old hau tree with a a honey bee nest. And I didn’t know at that time that bees stung. But they never bothered me. So, I’d go with a stick after dinner, and after I had my egg, I’d go to the tree and with a stick, I’d scoop up the honey and eat it right there.

[CHUCKLE] Now, the camp where you lived was an unusual camp in that it was all members of the luna class, the managers.

Yes. Except for my father, who was the stable master. So, he had a special function, which categorized him as a member of the uh, community.

So, luna of the horses.

Correct. [CHUCKLE]

So, did you get to know how to ride, how to take care of horses yourself?

I did. As a matter of fact, the horses became my own, you know, in my mind, because I was able to ride them any time I wanted to. Because it was in the pasture right across me, and I could jump on the horses. They were well- behaved, they weren’t unruly, so I could jump on ‘em and pat ‘em, and they’d take me for a ride around. That’s another well-kept secret. My mom would never allow me if I told her I was riding the horse.

Where did your parents come from?

My dad came from the Philippines, emigrated to Hawaii at the young age of fourteen years old.

What made him do that? Was he escaping something, or was it the lure of something ahead?

I never really talked to my dad, but he, like many other Filipino immigrants had a dream, and they chased this dream all over, of coming to Hawaii, making a fortune, and then eventually going back to the Philippines. And I think in my father’s case, he started a family and his dreams of returning back to the Philippines was gone, because he had all these beautiful kids; right? [CHUCKLE] My dad was very easygoing. He was the type of guy that would let you do almost anything. He was very resourceful.

Was it your father who gave you your middle name?

Yes; yes. I was born on the 30th of December, 1938, and my middle name is Jose, named after the nationalist hero of the Philippines.

A revolutionary, and social reformist.

He was a revolutionary; right. And I never knew it at that time as I grew up, but later, I got to appreciate who Jose Rizal was, and also very proud of my middle name, which I wasn’t before.

Your mom was a local girl?

My mom was a local girl, and she grew up in a place called Kapahi, and Eleele. At the time that she was in Eleele, her mom had separated, and my grandfather at that time, who was [INDISTINCT], was actually the sole parent taking care of her. But he had to work. And she was very young at that time, maybe one or two, or three years old. And so, my grandfather actually took my mom to work with him, and put her in this, you know, big uh, barrel. And she stayed there all day. [CHUCKLE]

Wow!

It was amazing. But that’s what she did on a daily basis. I didn’t find that out until she was ninety-three. She never talked about her childhood.

She grew up daytimes in a barrel, while her grandfather worked.

Yes; yes.

Wow.

And she continued doing that until she actually moved. I guess my grandfather at that time went back to the Philippines, so she had to join her mom at that time, who had remarried. And then, she became, I guess, the caretaker for her siblings when her mom left again. [CHUCKLE]—

How many siblings?

She had a total of six.

Six siblings?

Yeah.

Your mom does sound amazing. And then, when she married your dad, they also had children. Where did the six siblings go? Were they all grown up?

They lived with us.

Is that right?

So, we had eleven, plus my mom and dad.

Wow.

That was quite a treat.

And you were the youngest.

I was the youngest; I was the preferred one.

As America prepared to enter World War II, there were no longer just horses in the pastures at Kapaa Stables. United States Army soldiers moved in, and young Ed Gayagas spent time visiting with them. From this experience, he knew he wanted to be a soldier when he grew up.

The soldiers bivouacked in the pasture across us in 1941 and 1942.

They were waiting to be staged to some other war location?

They were scheduled to be deployed, and knowing my Army information now, the size of the unit was probably close to a battalion or at least three company- sized units. And Leslie, for the first time, I was surprised that the people I saw were ones that I had never seen before; they were white and they were black. I had never seen so many white and black together, and looking at them, I was in awe, because I had never seen any of ‘em. They looked a lot older; they were probably nineteen to twenty-one.

And how old were you then?

I was three years old.

I think you came to know them. How did that happen?

Well, we got to visit quite often. After dinner, usually, I’d mosey on to the pasture.

By yourself?

By myself.

At three years old?

I was not authorized to go there, but I was also rambunctious; I was also hasty in my decisions. If I thought about doing something, I did it. And so, I went into the pasture; I met these uh, soldiers. I enjoyed their company; they were very cordial, very courteous.

You were a toddler at the time?

I was a three-year-old and running around, you know, like nobody’s business.

Because in those days, there wasn’t the kind of helicopter parenting that we often have now.

No; and you know, we didn’t have a door to lock. The car had no switch turn with a key, and everything was open for everybody. Except that my mom was very protective, and she said, No, you can’t go into the pasture. So, she let me walk around, but she couldn’t keep track of me all the time. And so, I did go into the pasture; I did talk to the soldiers. I got to meet some of ‘em. I don’t remember their names, but what I do remember was their courtesy, their kindness, and their demeanor. They were soldiers; they were gentlemen. They were very nice. And not only that, they gave me C-rations. [CHUCKLE]

That’s a devious treat.

Well, a lot of people don’t like C-rations, but for me, I enjoyed the the meals that they had in the can, the candy that they had accompanying the meals. And they also had cigarettes. So, I started smoking at a very young age. [CHUCKLE]

Again, are you saying three years old?

Three years old; I started smoking. And I didn’t like the smoking at first, because my dad introduced me to toscani. It’s raw tobacco, and very, very strong. I didn’t like that. But the cigarettes were a milder thing. [CHUCKLE]

You did start smoking young.

I did. But that was only while the soldiers were there. I never picked it up as a habit.

They must have loved having this little kid visit as their mascot.

They did. I think they actually enjoyed my company, because it was a break from the routine of cleaning their weapons and talking to each other. And seeing a little kid that they could talk to was probably enjoyable for them, entertainment.

And did that encounter or, you know, encounters over time with them in the pasture; did that have a lasting effect?

It did. It told me I wanted to be one of ‘em. I did. And that goes back to December 8th. Now, this was a few months before, at the start of World War II when we got together as a family, knowing that President FDR was gonna make a speech. So, we gathered around the radio, and FDR made the proclamation of war, and that was followed by his statement that, now, this war is gonna be something that every … husband, every wife, every mom, every dad, son and daughter will be a part of it. And then, that was followed by a solicitor that said, Okay, we need volunteers; we need volunteers to fight this war, to build war machines and so forth and so on. And I turned to my mom and I said, Mom, I’m gonna join; I want to join. And of course, you know, the answer was, No. And so, I remembered that all the way through. And then the second influence was the troops, the soldiers that were in the field, in the pasture, that impressed me to no end. And I wanted to be a soldier so bad.

Did you ever deter from that? Did you always intend to be a soldier?

Absolutely.

Never wanted to be, you know, the usual fireman, cowboy?

No.

No?

No. I wanted to be a soldier, all the way. And my first opportunity was when I was sixteen years old. Everyone was joining the National Guard; my brother, my good friends; they were much older than I was, and they joined the National Guard. I said … I gotta do it, too. [CHUCKLE] So, I joined at sixteen.

Was that legal?

No. I signed my mom’s signature, and it wasn’t found out until I made seventeen, and I had to report to the local draft board, at which time they found out I was only seventeen. But I was old enough then where they could retain me, but I got a good butt-chewing as a result of that. I never regretted that decision, because I enjoyed every minute of it.

After finishing high school, Ed Gayagas wanted to attend college, and the Army also beckoned. A timely letter and some advice from a mentor gave Gayagas an opportunity that he has never forgotten.

[MUSIC]

You talked about your impulsivity and being kolohe. You got kicked off of your school basketball team.

Yes. I was on the championship team, the first time ever that Kapaa High ever won a championship. [CHUCKLE] And we were in Castle High School, and I met a few cheerleaders. And we got in the car, and one of ‘em offered me a cigarette, and I took it. So, when we got back to Kapaa, the team assembled on the basketball court, and I was called forward. I said, Oh, no sweat; coach wanted to talk to me. And the first question he asked me was, Did you smoke? I said, Yeah, I did. I wasn’t gonna lie; I never lied. [CHUCKLE] And so, he says, You’re off the team. From there, my next stop was Auntie Gladys Brandt’s office. She did not have to say a word. All she had to do was look at you … and yeah, you would [CLEARS THROAT] straighten out [CHUCKLE] and you would say, Uh-oh, I’m in trouble. Which I was, and she did talk to me. And I think her manner of dealing with youngsters like me was not to give me criticism. I think she knew me better than I knew myself. She didn’t give me criticism or scold me at that time. You know what she did? She gave me encouragement, which kinda stimulated me. So, after I walked out of her office, I said, You know, I’m not gonna take this laying down. So, I joined the senior league basketball, and I learned a lot; I learned a lot from ‘em. And as a result of that amount of time that I spent with the senior league, I learned the techniques of shooting a ball a lot better, dribbling, and dunking. When I graduated from high school, I was hoping that I could get into the University of Hawaii. I knew I wanted to do West Point because of MacArthur, and you know, being the hero for the Filipinos, and I said, I want to be just like him. But my dreams were shot down right away by the counselor saying, You don’t have enough math background, you don’t have the language skill, so don’t even try. Those were the words he used.

Did those words inspire you to do it anyway?

Yes; I said, I want even more to be a soldier. So, I applied to the University of Hawaii. After graduation, I waited, and waited. And then, the call for the all- Hawaii company came up. My classmates were going, and I said, I’m not staying back, I’m gonna do it with you. So, we got in a bus, caught the DC3, came to Honolulu, another forty-five minutes. We went to the YMCA, took our physical, did the written exams, and I passed with flying colors. And then, the sergeant says, Okay, you’re gonna be our future leader, and I’ll see you in a week for your swearing in. So, we got on the plane again back to Kauai. And the first thing I did was, I wanted to check out my mail to see if I have anything from the University of Hawaii. So, I went to Box 55 in Kapaa, and there was a letter in there. I opened it, and it said, You have been accepted to the University of Hawaii. Wow! I must have jumped ten feet high then. [CHUCKLE] And not only that, the letter continued on and said, You also will receive a scholarship in basketball and track.

I encountered the first obstacle in registering when they said, Hey, you don’t speak English. I said, I speak fluent Pidgin. [CHUCKLE] I’m from Kauai; that’s the center of Pidgin. But they said, No, you’ve gotta take remedial speech. And so, I had to do that for three years straight. So, it wasn’t an easy road for me. But after a while, I started to enjoy the speech classes.

Did you think you spoke really heavy Pidgin?

I didn’t think so, but apparently, someone from Honolulu said I did. [CHUCKLE]

When Ed Gayagas graduated from the University of Hawaii, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army. One of his first assignments in 1962 was to give martial arts training to Army Rangers who were preparing for a possible confrontation with Cuba.

My first assignment was Fort Campbell, Kentucky. As soon as I arrived in Fort Campbell, we were sequestered because of the Cuban Missile Crisis. My commander at that time saw that I had some martial arts background. So, he said, Lieutenant Gayagas, I want you to do something here. We have a bunch of Rangers, mostly from West Point, who have not had any martial arts training, and if we were to deploy right now, we’d have an envelopment attack into Cuba. [CHUCKLE] I said, Wow. I hadn’t expected that, because I wasn’t airborne qualified at that point. I actually did qualify, but the Rangers that we were talking about who were not trained in the martial arts had to do something for a month and a half while we were sequestered. And so, Colonel Storey advised me that I should be training them in martial arts and self-defense, which I did. And it gave me so much satisfaction to be training people who were from West Point and who actually wanted to learn the martial arts.

And they were Rangers; they were proficient in many, many other things.

But not martial arts, and not self-defense combat. And so, I got a lot of enjoyment out of that, and I got a lot of respect as a result.

Ed Gayagas later went on to serve in the Vietnam War as a logistics officer in a military hospital, and retired from the United States Army as a colonel in 1989. His devotion to his family and his community has stayed with him through his life.

[MUSIC]

I became a general contractor right after I retired. And I found out, hey, I don’t need the money and my wife’s going on vacations by herself; so I said, I’ll become a consultant, then. That was just as bad. So, I stopped doing it, and then I became a fulltime volunteer for the University of Hawaii, the Alumni Association, the Athletics Department for basketball and track.

This is also very time-consuming; right?

It was.

If it’s fulltime.

It was a lot of fun. [CHUCKLE] And so, the third thing I did was to volunteer for ROTC. We had the organization put together, and I became the president. And after that, I couldn’t find anybody else to replace me, and I’ve been doing it for fifteen years. [CHUCKLE]

You’re a very competitive guy. Even when you had a bad virus, you ran the marathon.

Yes.

And you made it all the way through, instead of … you know, everyone would have understood, you know, gracefully bowing out. But instead, you were throwing up throughout the race.

Well, I had my daughter with me, and she had trained me for nine months. There was no way I was gonna stop anywhere and say, No, I quit. Besides, that’s against my warrior ethos.

Did you run the next year?

No; that was my first and last. But I will continue to run the Aloha Run and support the great program that Carole Kai has, supporting over two hundred charities.

When you look back at your life, you know, you started off in Kapaa, and you’ve now traveled the world, and had a lot of influence in your life. What do you think then you think of how far you’ve come?

I gotta say I’m fortunate. Most of all, I have to thank my family; my family, my wife. She’s really the backbone of the whole family. She’s done everything for me, for the kids, and she’s tolerated everything I’ve done.

Ed Gayagas’ son Lincoln, and one of his daughters, Crissy, fulfilled their father’s dream by attending West Point. Crissy Gayagas served in the Army for nearly twenty-four years, and like her father, achieved the rank of colonel before retiring. Lincoln Gayagas rose to the rank of captain in the Army, and is now an engineer at Fort Shafter. Ed Gayagas’ other daughter, Cathy, works for the City and County of Honolulu. Ed Gayagas’ irrepressible attitude and positive outlook on life continue to drive him today, through his volunteer contributions to our community. Mahalo to retired colonel Ed Gayagas of Aiea for your service to our nation and to our community. And mahalo to you, for joining us. For PBS Hawaii and Long Story Short, I’m Leslie Wilcox. A hui hou.

For audio and written transcripts of all episodes of Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox, visit PBSHawaii.org. To download free podcasts of Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox, to the Apple iTunes Store or visit PBSHawaii.org.

I kinda had the old bushido code; you know, the warrior spirit of Japan. I was brought up that way, that the boy also always had the priority. And you know, myself, I had a very, very difficult time walking, holding my wife’s hand. I always had to be a step ahead of her. So, I had to overcome that.

How did you get over it?

I guess being exposed to the American way of life and the custom. But if I stayed back here in Hawaii, I probably would have not changed as much. But traveling all over the world, I think I learned a lot of different ways to live life better.

[END]